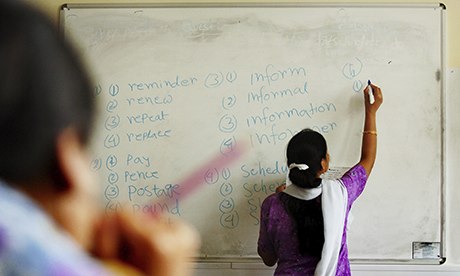

What can language teachers in the UK learn from TEFL techniques? Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

Ellie Colegate spent five years studying French at school in Kent, but opted not to continue beyond Year 9. “Learning a new language was never something my teachers made appealing or entertaining. My experience was purely an academic one. My French teacher just made us copy and complete exercises from books. And this is a top set French class.”

Colegate, 15, has taken some of her GCSEs early and is already looking ahead to a bright future at university, but it’s clear that the British approach to language education has failed to engage her. “During lessons, my teacher spent little time speaking the language herself and she would only ever get a handful of the best students to speak in class.”

After three years or more studying a foreign language at secondary school, the majority of British school leavers are unable to read, write, speak or understand more than a few phrases, pre-learnt and repeated until they can be said on command, parrot-fashion.

At the same time, the industry around Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) is exploding with activity and seeing increasing success across the globe. TEFL teachers teach English abroad to people whose first language is not English. There are TEFL courses – sometimes also referred to as TESOL (Teaching English as a Second or Other Language) – across the globe, offered by a number of accredited course providers. The British Council estimates there are 1.55 billion English learners around the world, and at least 10.2 million English teachers. There are more than 100,000 native English speakers teaching in China alone.

How is it that the TEFL industry is booming while the British language learning system is in a state of crisis?

Deena Boraie is president of the TESOL International Association and dean of continuing education at the American University in Cairo, and she believes that methodology is what makes the sector different – and successful. “The field of teaching English to speakers of other languages really is a unique discipline with its own pedagogy [and] it combines a number of academic areas,” Boraie explains.

Italian student Caterina di Mascio, 19, has learned most of her English through TEFL-based techniques. “Learning English with a native teacher isn’t like formal education,” she says. “It’s fun and interesting, and your teacher becomes your friend.” The characteristic TEFL emphasis on spoken language quickly breaks down inhibitions and forces each student to pay close attention throughout the lesson. This style of learning and teaching could have made all the difference to Colegate’s perception of languages.

Benny Lewis, a travel blogger who teaches English, has created an entire brand from examining different ways to master languages with his website Fluent in 3 Months. He believes the TEFL approach is successful because it emphasises alternative elements of language learning.

“TEFL teachers are forced to step outside of a failed academic system that never helped them speak a language at school, and do things completely differently,” he explains. “Learning a language can indeed be fun and not all about grammar, vocabulary, mistakes and feeling stupid.”

The secret to TEFL methodology is simple: teachers create natural situations for students to interact in. Every student speaks throughout the lesson, and physical movement is exploited to avoid boredom and fatigue. The experience of a TEFL student is completely different to that of a British language student. Traditional grammar tables and confusing linguistic terminology are often abandoned, but that doesn’t mean it gets ignored. “Grammar is explained by use of examples in such a way that it doesn’t feel like grammar,” says Lewis. “It can and likely must be taught, but in a communicative context.”

Speaking becomes easier if the physical setup of a classroom allows direct communication between teacher and student, and interaction between students. TEFL teachers aim for a democratic atmosphere by organising desks in a horseshoe shape or “cafe-style”, rather than arranging a classroom in monotonous rows. Sometimes teaching doesn’t happen in a classroom at all. Wherever it’s happening, TEFL targets an inclusive, friendly and open working space.

But the is – to some extent – dependent on delivery by a native speaker. “It’s easier and less exposing for non-native speakers teaching a language to hide behind a text book or grammar book than it is to engage in activities a TEFL teacher would engage in,” says Johnny Harben, who has taught English as a foreign language in the UK and abroad for the past five years. “Unless somebody is absolutely fluent, there’s always the temptation to speak in a common language with students,” Harben adds. “The TEFL methodologies are absolutely for the native English speaker.”

Carol Syder, director at The English Experience School of English in Norwich, and agrees that immersion with a native speaker is an integral part of the process. “We only employ English mother tongue speakers at both our school in Norwich and on the camps we run abroad every year. Why? Because this is the best way to ensure that the students gain confidence and it gives them the best opportunity to improve their language skills in a short space of time.”

They key component to TEFL’s triumph seems to be in the immersion concept. This is echoed by students and teachers, and was the conclusion of a 2008 report on the SCILT. Early Primary Partial Immersion (EPPI) programme that took place in Aberdeen. The EPPI scheme was characterised by teaching children in two languages from their first year of primary, and it marked the first time the model had been applied in a UK school.

Pupils who took part consistently exceeded national reading targets for their age and achieved better academic results than their peers who did not participate in the scheme. Most importantly, students who took part were openly enthusiastic about languages and wanted to continue studying French. Despite its success, the scheme lost funding after its three-year inaugural run. Yet these are the programmes with the potential to signal real change in British language education.

Hannah Garrard taught in South Korea for two years. She believes communication and temperament are pivotal. “Trying to communicate can be an embarrassing experience for both student and teacher [in TEFL], so you really have to bring your personality to each lesson,” she says. “I got to know my students and established what they wanted from their learning. I asked what they wanted to know about in terms of subject, and built the technical language skills from there.”

Immersion and communication are the buzzwords and concepts that could drive British language education forward. “Immersion pushes students to find lateral solutions to problems,” Garrard says. “They have to think ‘how am I going to make myself understood?’ so communication and problem-solving are taken – quite naturally – to the next level.”

KOMENTAR ANDA